Sir Joshua Reynolds, Three Ladies Adorning a Term of Hymen 1773. Tate.

The Exhibition Age 1760–1815

17 rooms in Historic and Early Modern British Art

The first public exhibitions bring new audiences and new status to British art. This gallery recreates the spectacle of these early displays

The first temporary exhibition of contemporary art opens in London in 1760. Many more soon follow, notably the annual summer exhibitions held from 1769 by the new Royal Academy. For the thousands of visitors attending, these exhibitions can be overwhelming, unruly experiences. Noisy, hot and overcrowded, people come for the spectacle as much as for the art. They are as bursting with paintings as with people. As in this room, the pictures are densely hung from floor to ceiling in a kaleidoscope of styles and subjects.

For artists, this brings new challenges and opportunities. They worry that their work cannot be seen properly in the crowded conditions. To stand out against the competition, they bring ever greater individuality, experimentation and even flamboyance to their work. Art becomes regularly talked about in the newspapers, and reviews from critics can make or break careers.

Exhibitions become fashionable events. Artists are able to directly address more people than ever before, beyond a small number of elite patrons. To engage this wider public, their work often reflects popular interests and current affairs. Exhibitions become places where the nation’s ideas and anxieties are expressed.

There is a new buzz around British art. A sense of national identity is projected through these exhibitions. They help define a ‘British school’, which is celebrated as a sign of the nation’s cultural wealth and progress. Exhibitions contribute to how the country imagines itself on the world stage.

Francesco Zuccarelli, A Landscape with the Story of Cadmus Killing the Dragon exhibited 1765

This painting illustrates the story of Cadmus, founder of the ancient city of Thebes, as told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Cadmus is slaying the dragon that has killed his companions. They have died trying to collect spring water from the dragon’s cave, not knowing that it is sacred to the god Mars. Cadmus is protected by a lion-skin and armed with a javelin. The Italian painter Zuccarelli left Venice for London in 1752, his mythological landscapes popular with British patrons. In 1768 he was commissioned to produce works for George III, and was a founding member of The Royal Academy.

Gallery label, February 2016

1/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Three Ladies Adorning a Term of Hymen 1773

Joshua Reynolds paints the aristocratic Montgomery sisters, Barbara, Elizabeth and Anne, decorating a classical sculpture with flowers. Their poses associate them with the mythological Graces, personifying charm, grace and beauty. This emphasises the sisters’ beauty and elegance and may also playfully allude to their fame as ‘The Irish Graces’. By including the statue of Hymen, the Greek god of marriage and fertility, Reynolds also celebrates their desirability for marriage. Reynolds exhibited this painting in 1774. It exemplifies his ‘grand style’ of portraiture, which drew inspiration from classical and Renaissance art, and favoured idealised elements rather than current or specific fashions. The painting prompted one art critic to praise Reynolds’ ‘great Richness of Imagination’.

Gallery label, February 2024

2/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Sir David Wilkie, The Bag-Piper 1813, exhibited 1813

David Wilkie had already made his name in the London art world when he painted this small picture. It shows a bagpiper seemingly lost in thought, his fingers poised to play. One early biographer claimed this subject had been in Wilkie’s mind since boyhood and includes the old kirk (church) of his hometown, Cults, in the distance. While this is debatable, the explicitly Scottish subject is unusual in Wilkie’s work at this time. He exhibited this painting at the British Institution in 1813. While this may reflect his hope to raise the status of Scottish art, The Bag-Piper also appealed to a romanticised image of Scotland.

Gallery label, February 2024

3/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

George Romney, A Lady in a Brown Dress: ‘The Parson’s Daughter’ c.1785

George Romney was one of London’s most fashionable portraitists. He was particularly admired for the charm and simplicity of his female portraits. He chose not to exhibit his works publicly after 1772, instead relying on word of mouth for private commissions. Romney became known for his virtuoso ‘performances’ at sittings, quickly painting the sitters’ likeness directly onto the canvas. This painting demonstrates the artist’s loose, expressive brushwork. We do not know the identity of the sitter, but later, in the second half of the 19th century the work became widely known as ‘The Parson’s Daughter’.

Gallery label, February 2024

4/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Sir Thomas Lawrence, Philadelphia Hannah, 1st Viscountess Cremorne exhibited 1789

Lady Cremorne is shown standing confidently, gazing directly out at the viewer. This seems apt given her high social standing: she was lady-in-waiting to Queen Charlotte and her grandfather was William Penn, who established the British colonial settlement in Pennsylvania, America. Thomas Lawrence was only 19 when he painted this imposing portrait, and it was his first full-length painting. He included it among his exhibits at the Royal Academy in 1789, where it caught the press’s attention. Lawrence was heralded as the successor to the aging Joshua Reynolds. Soon after this, Lawrence painted Queen Charlotte, a prestigious commission perhaps suggested by Lady Cremorne herself.

Gallery label, February 2024

5/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Sir Nathaniel Dance-Holland, The Meeting of Dido and Aeneas exhibited 1766

This picture shows the meeting of the Trojan prince Aeneas and the Carthaginian queen Dido, from Virgil’s epic poem, the Aeneid. Aeneas was shipwrecked near Carthage after the sack of Troy. The goddess Venus made Dido fall in love with him and helped him to hide in her citadel. He watches Dido welcome his fellow Trojans and when she asks to see their ‘king’ the mist clears and Aeneas reveals his identity. Dance-Holland made this picture while he was in Rome and sent it to London to be exhibited as a way to advertise his imminent return to Britain.

Gallery label, February 2016

6/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Henry Monro, The Disgrace of Wolsey exhibited 1814

Henry VIII stands commandingly on the left, handing papers to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. This signals Wolsey’s downfall – as the King’s chief adviser he failed to secure the annulment of Henry VIII’s first marriage, ultimately leading to his arrest for treason. While a historical subject, Henry Monro drew his inspiration from Shakespeare’s play Henry VIII. He worked on the painting over 5 months in late 1813, employing ‘Ben’ from the local workhouse to model as Wolsey. Monro had been an ambitious young artist, and when the painting was exhibited at the British Institution in 1814 after his early death in March that year, it secured Monro’s celebrity.

Gallery label, February 2024

7/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Henry Walton, A Girl Buying a Ballad exhibited 1778

This painting shows a fashionable young woman approaching an old ballad-seller on the street, whose printed wares are pinned up behind him. Henry Walton exhibited this painting at the Royal Academy in 1778. He likely hoped this imaginative image of city life would appeal to exhibition-goers. But he may also have intended a political reading too. The two portrait prints on the right are recognisable as General William Howe and his brother, Admiral Richard Howe. Their doubts about Britain’s war with Revolutionary America had recently led them to resign from military command. This was highly topical as the war was hugely controversial in Britain.

Gallery label, February 2024

8/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Angelica Kauffman, Portrait of a Lady c.1775

Angelica Kauffman was hugely successful – by the 1770s, her work was so popular that one contemporary quipped, ‘the whole World is Angelica-mad’. In portraits like this, Kauffman helped establish and promote an image of feminine creativity and intellect. While we do not know the sitter’s identity, the writing instruments she holds emphasise her learning, perhaps even signalling literary ambitions. The book and statue of Minerva (the Roman goddess of wisdom) on the table, further underline this. Dressed in classicising robes, she looks confidently out at the viewer. Such images also reflect the strong network of women – patrons, fellow artists, intellectuals, and professionals – that Kauffman relied upon throughout her career.

Gallery label, February 2024

9/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Richard Cosway, Portrait of a Gentleman, his Wife and Sister, in the Character of Fortitude introducing Hope as the Companion to Distress (‘The Witts Family Group’) 1770

Although principally a portrait miniaturist (see cabinet 2: The Portrait Miniature in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries), Richard Cosway also produced some larger-scale works in oil. This allegorical portrait was painted following the death of a young London linen draper, Broome Witts, in 1769. Witts is shown here in the role of Fortitude, introducing his sister Sarah in the guise of Hope (left) to his wife Elizabeth, depicted as Distress. This memorial image was presumably commissioned by one or both of these ladies.

Gallery label, August 2004

10/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Richard Westall, The Reconciliation of Helen and Paris after his Defeat by Menelaus exhibited 1805

This painting is inspired by Greek legend: Helen was married to Menelaus, king of Sparta. Her affair with the Trojan prince, Paris, led to the Trojan War. Richard Westall painted this scene for Thomas Hope, a wealthy collector. His London home had rooms designed and furnished in the different styles of the ancient world – Egypt, India, Greece and Rome. Westall modelled the figure of Helen on a Greek statue in Hope’s collection. In the 1790s Westall’s Royal Academy exhibits were the talk of the town. His flashy paint effects divided opinion, however, and many thought his work was too stylised and unnatural.

Gallery label, February 2024

11/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

George Dawe, Naomi and her Daughters exhibited 1804

This scene is from the Old Testament: Naomi, in the centre, encourages her two widowed daughters-in-law to return to their people rather than accompany her to Bethlehem. George Dawe shows the moment when Orpah (left) leaves weeping, but Ruth (right) clings to Naomi and refuses to go. This was the first painting Dawe exhibited at the Royal Academy. By demonstrating his ability to paint emotive and high-minded subjects, Dawe likely hoped the painting would help him stand out as a talented newcomer. The restrained colours, sculptural style and idealised figures were popular with painters at the time.

Gallery label, February 2024

12/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

John Opie, A School 1784

This painting caused a sensation when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1784. It was remarkable for its frank and touching representation of ordinary life. John Opie modelled the school mistress on his mother. Contemporary viewers particularly admired its realism and dramatic light effects. John Opie launched into the London art world as the ‘Cornish wonder’, a self-taught prodigy. This picture only added to his celebrity. The popularity of A School – and condescension towards Opie because of his working-class background – is apparent in one critic’s quip that ‘Could people in vulgar life afford to pay for pictures, Opie would be their man’.

Gallery label, February 2024

13/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Henry Robert Morland, A Laundry Maid Ironing c.1765–82

This painting of a maid ironing is typical for Morland, who specialised in such ‘fancy pictures’ - subjects drawn from everyday life but with imaginative elements. He repeatedly painted and exhibited idealised pictures of young women in working-class roles, as ballad singers, oyster sellers and laundry maids. Here, the woman is shown passively gazing down, serene as she works, her tools and appearance pristine. There is little indication of her individuality, or of the real hardship of such domestic labour. Instead, she represents a contrived ‘type’, made attractive for contemporary middle and upper-class viewers and saleable for the print market.

Gallery label, June 2022

14/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Francis Cotes, Portrait of a Lady 1768

This elegant and ornamental portrait

is a fine example of Cotes's style, which emphasises fashion rather than character. The sitter, whose identity is uncertain, sits on a garden bench in an artificial yet striking pose. Her gown and its lace are arranged decoratively about her, the pink and white colouring echoed by the foxgloves behind her, and the roses on the left. The portrait was painted in 1768, the same year as the foundation of the Royal Academy. Cotes was one of its founder members, which his prominent signature on the tree trunk, 'F Cotes RA px', proudly announces.

Gallery label, February 2010

15/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Francis Cotes, Anna Maria Astley, Aged Seven, and her Brother Edward, Aged Five and a Half 1767

The children in this portrait were the offspring of wealthy baronet and landowner Sir Edward Astley and his second wife Anne Milles. They are depicted at play on a classical terrace, reminiscent of the family’s grand estate at Melton Constable, Norfolk. Anna Maria, who waves her brother’s plumed hat above her head, died in childhood, the year after this portrait was painted. Edward, whose elder half-brother was to inherit his father’s title, lived to carve out a successful career as a soldier in the British army. It is thought that the portrait was commissioned by the children’s maternal grandfather.

Gallery label, February 2010

16/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Johan Zoffany, The Bradshaw Family exhibited 1769

Small-scale group portraits like this, known as ‘conversation pieces’, projected an idealised vision of family life. This picture employs a pyramidal arrangement of the figures to express the structure of the family. Thomas Bradshaw (1733–74), a senior civil servant and politician, is shown at the apex of the pyramid. His family is arranged below him. The two women are Bradshaw’s wife, Elizabeth on the right, and, on the left, probably his sister. The two oldest sons are shown at the far left and right of the group. Their position in the composition serves to associate them both with the sheltered space of the family unit, and the outside world.

Gallery label, February 2016

17/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Benjamin West, Pylades and Orestes Brought as Victims before Iphigenia 1766

This painting’s story is based on a play by the classical author Euripides. The two semi-naked men have been arrested for trying to steal a gold statue of the goddess Diana from the temple. They have been brought before Iphigenia, a priestess of Diana, to be sacrificed on the altar. But here Iphigenia recognises the man in the red drapery as her long-lost brother, Orestes. The composition of this picture was heavily influenced by the artist’s studies in Italy. He particularly admired the sculptural friezes on classical tombs and the Renaissance frescoes of Raphael.

Gallery label, February 2016

18/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Colonel Acland and Lord Sydney: The Archers 1769

This portrait depicts two young aristocrats. Dressed in quasi-historical clothing invented by the artist, they are mimicking a medieval or Renaissance hunt; the dead game they leave in their trail underlining their noble blood and aristocratic right to hunt. This painting celebrates their friendship by linking it to an imaginary chivalric past, when young lords pursued ‘manly’ activities together against a backdrop of ancient forest. The subjects are shown in perfect harmony – at one with each other and joint masters over nature.

Gallery label, February 2016

19/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

George Stubbs, Mares and Foals in a River Landscape c.1763–8

This painting seems to have been used as an ‘overdoor’, hung with two other pictures by Stubbs above the doors in the dining room of George Brodrick, 3rd Viscount Midleton, MP (1730–65). Reflecting the ornamental use to which this painting was to be put, it seems that Stubbs, the premier animal painter of his day, did not set out to be especially original. The figures of the horses are the same as those appearing in another painting, a commission for Lord Rockingham representing specific horses owned by him, although the colour of one has been changed from brown to grey.

Gallery label, February 2016

20/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

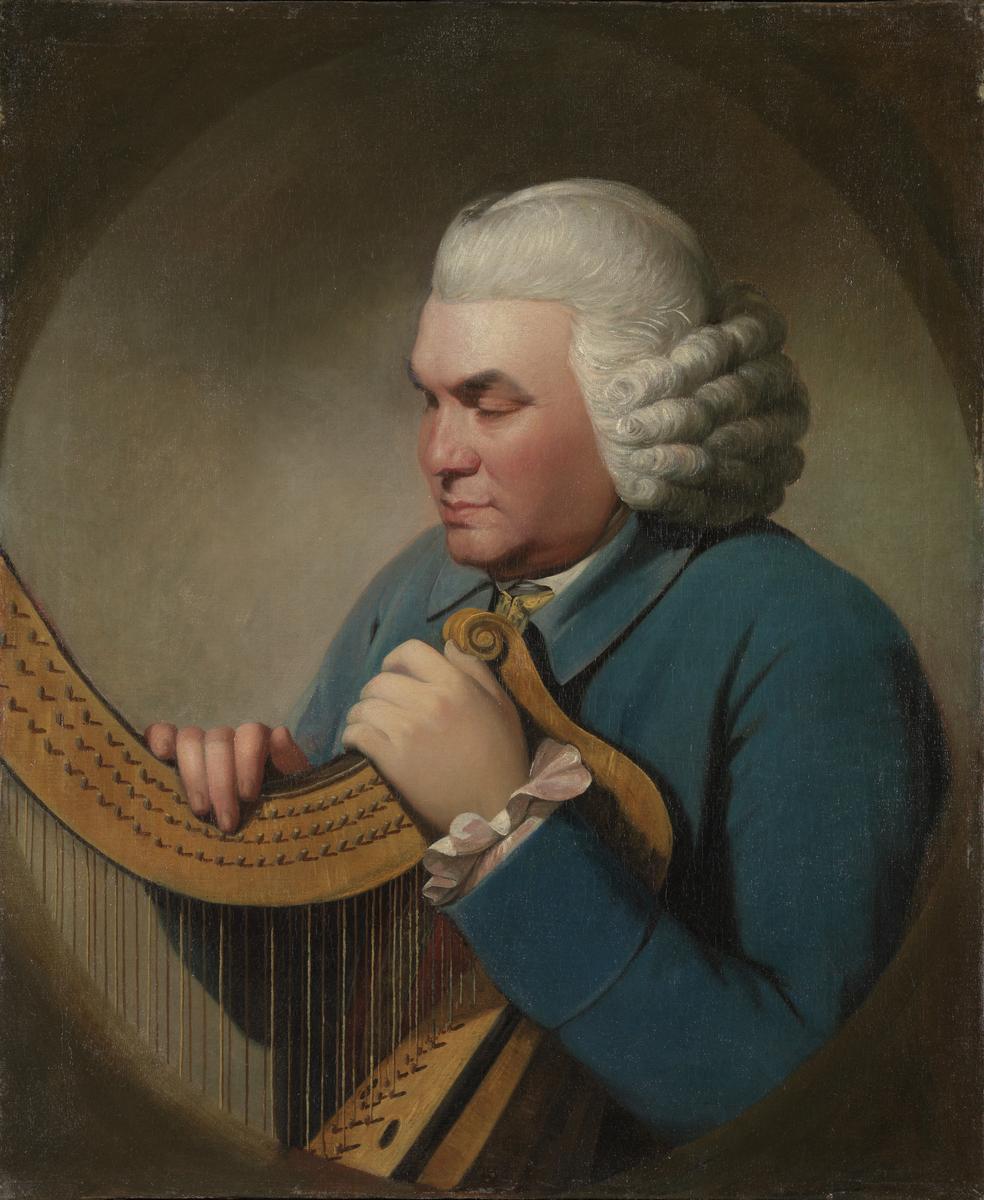

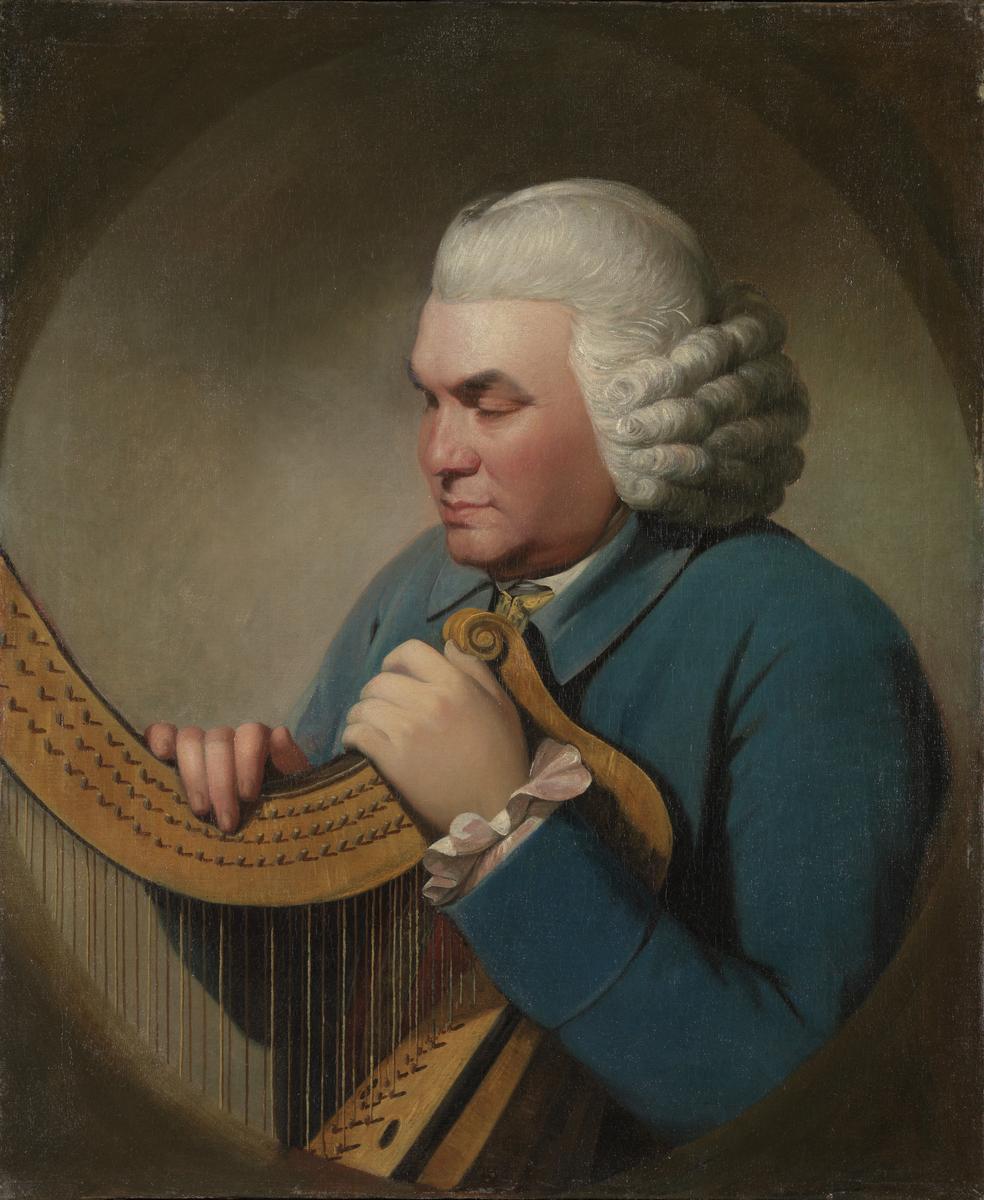

William Parry, Portrait of John Parry Holding his Harp 1780–90

This portrait shows the celebrated Wesh musician John Parry, sensitively painted by his son William Parry. John Parry’s reputation as ‘the famous blind Harper’ is visualised here – he is shown with his eyes closed (as was conventional for blind sitters) and holding a Welsh triple harp. Rather than playing this instrument, John’s hands rest on top and he appears lost in thought. This may allude to his perception of the world through his other senses, like touch and sound. John’s deep contemplation also evokes the poetic, other-worldly nature of music, associating him with the popular, romantic image of the Welsh bard. This might be the portrait William Parry exhibited in 1787 as a posthumous tribute to his father.

Gallery label, October 2023

21/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

George Dawe, Imogen Found in the Cave of Belarius exhibited 1809

George Dawe depicts a scene from Shakespeare’s play Cymbeline. Imogen – the heroine and daughter of Cymbeline, the ancient king of Britain – escapes court and disguises herself as a young man. Here, Dawe shows the moment when the character Belarius (left) and Imogen’s two long-lost brothers (right) discover her in a cave. They believe she is dead, but she has actually just drunk a sleeping potion. Dawe mainly painted portraits, but here ventures into ‘history painting’ (images of biblical, mythological, literary or historical subjects). This was regarded as the highest genre of painting at the time and indicates Dawe’s ambitions as an artist. With its high-minded literary theme and dramatic lighting, this painting was meant to stand out when it was first exhibited at the British Institution in 1809.

Gallery label, October 2023

22/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Benjamin West, Cleombrotus Ordered into Banishment by Leonidas II, King of Sparta 1768

Benjamin West showed this painting at the second exhibition of the newly formed Royal Academy. After several years in Italy, West had established himself in London as the leading painter of subjects from classical history. His example, and the Academy’s teaching, encouraged numerous young British artists to study in Italy.

His subject is an incident from ancient Greek history. Leonidas, king of Sparta, was usurped by his son-in-law, Cleombrutus. When Leonidas returns looking for revenge, his daughter pleads for her husband’s life. Leonidas is moved by her tears, and commutes Cleombrutus’s death sentence to banishment.

Gallery label, September 2004

23/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Thomas Gainsborough, Sir Henry Bate-Dudley, Bart. c.1780

The Reverend Henry Bate-Dudley was one of London’s most notorious newspaper editors. He first rose to fame through his journalistic writing in the Morning Post, before establishing the best-selling paper, the Morning Herald in 1780, which was renowned for its social gossip and political attacks. Thomas Gainsborough was close friends with Bate-Dudley. Here, Gainsborough conveys Bate-Dudley’s self-assurance and perhaps his loyalty through including his adoring dog. For Gainsborough, their friendship guaranteed he was championed in the press. Such public support was invaluable in the competitive art world. That Bate-Dudley divided public opinion, however, is apparent in one critic’s pun about this portrait, remarking that ‘the man wanted execution’.

Gallery label, February 2024

24/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

John Opie, Portrait of a Lady in the Character of Cressida exhibited 1800

We do not know the identity of this woman, but she is probably a celebrity or actress who contemporary viewers would have recognised. Opie was working at a time when fame was becoming an increasingly important part of artistic success. This painting appeared at the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition in 1800. Artists jostled to grab public attention, painting more flamboyant and dramatic pictures. Opie depicts his sitter as the heroine of Shakespeare’s tragedy Troilus and Cressida.

Gallery label, October 2019

25/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Thomas Stothard, Nymphs Discover the Narcissus exhibited 1793

Thomas Stothard depicts a scene here from the Roman poet Ovid’s mythological narrative, Metamorphoses. The boy Narcissus, obsessed with his own reflection in the water, wastes away and turns into a flower. Here a group of nymphs discover the flower growing on the riverbank. The painting was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1793. Stothard’s steadiest form of income was book illustration, but his reputation as a history painter was beginning to grow in the 1790s. It was on this basis that he was elected a full member of the Royal Academy in 1794.

Gallery label, October 2023

26/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

John Hoppner, A Gale of Wind c.1794

John Hoppner was one of the leading portraitists of his day. When he exhibited this painting at the Royal Academy in 1794, it would have stood out to exhibition-goers as a highly unusual subject for the artist. Indeed, this is the only work Hoppner is known to have exhibited that wasn’t a portrait. We think the stormy seascape is set just off St Catherine’s Point in the Isle of Wight, an area known for its dangerous waters. The painting gave Hoppner an opportunity to show off his expressive brushwork and his ability to convey drama and narrative. Capturing a sense of the artistic competition of the time, one critic remarked: ‘The present aggression is incontestably bold, and well executed, and should be rewarded with a booty of reputation.’

Gallery label, February 2024

27/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

George Morland, Outside an Inn, Winter c.1795

George Morland was known for painting rustic country life. Here, he depicts a man departing from an inn, watched by a child from the open doorway. The traveller’s thick coat and shiny top hat suggests his affluence, in contrast with the humble inn keeper, who keeps a pig for food. The scene’s stark surroundings underscore the hardship of rural life. However, Morland may have been appealing to the popular market for simple, picturesque country scenes. At this time Morland began working on a smaller scale and often recycled compositions in order to increase his output. This painting is similar to an earlier print, and doorway exchanges regularly feature in Morland’s work.

Gallery label, February 2024

28/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

John Hoppner, Miss Harriet Cholmondeley exhibited 1804

29/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Charles Reuben Ryley, Oscar Bringing Back Annir’s Daughter 1785

Scotland’s legendary past, as told by the ancient Gaelic bard, Ossian, inspired this painting. It shows the famed warrior Oscar (in red), returning triumphant from battle to Annir, the elderly King of Inis-Thona. Oscar's victory reunites the king with his daughter. Ossian’s epic poem was published in 1765 and inspired many artists and writers. Nearly 60 Ossian subjects were exhibited in London between 1771-1830, including five pictures by Charles Reuben Ryley. However, the authenticity of the poem was soon questioned. The publisher, James Macpherson, had, in fact, invented the saga by blending Gaelic mythology with other sources and his own writing.

Gallery label, February 2024

30/30

artworks in The Exhibition Age

Art in this room

Sorry, no image available

You've viewed 6/30 artworks

You've viewed 30/30 artworks